A few weeks ago, the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) released the Kenya Poverty Report for 2022. This report is based on the 2022 Kenya Continuous Household Survey (KCHS), an annual poverty measurement survey. The surveys alone are an enormous undertaking including 24,000 households. These relatively new surveys fill a gap in what used to be household budget and expenditure surveys that happened only every 10 years. The good news is that we now know much more quickly how poverty is changing. The bad news is that the trend is reveals severe economic deterioration.

Globally, poverty reduction has stagnated since 2015. Recently, The Economist drew attention to this troubling trend and the lack of a robust global response. In Kenya, poverty is actually increasing. In a previous piece, I looked at changes in nominal consumption spending in Kenya between 2015/16 and 2021. Between 2015/6, median monthly consumption per adult equivalent had fallen 8% in nominal terms and 33% in real terms, with some of the largest declines happening in the top quintiles of the income distribution. Most of this decline was in the lead up to covid, not as a result of the pandemic, meaning people have been really struggling for several years now.

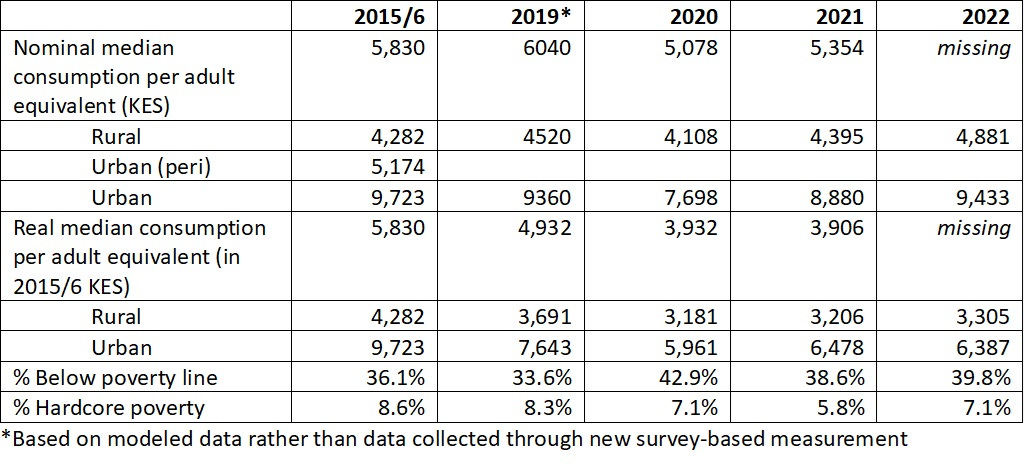

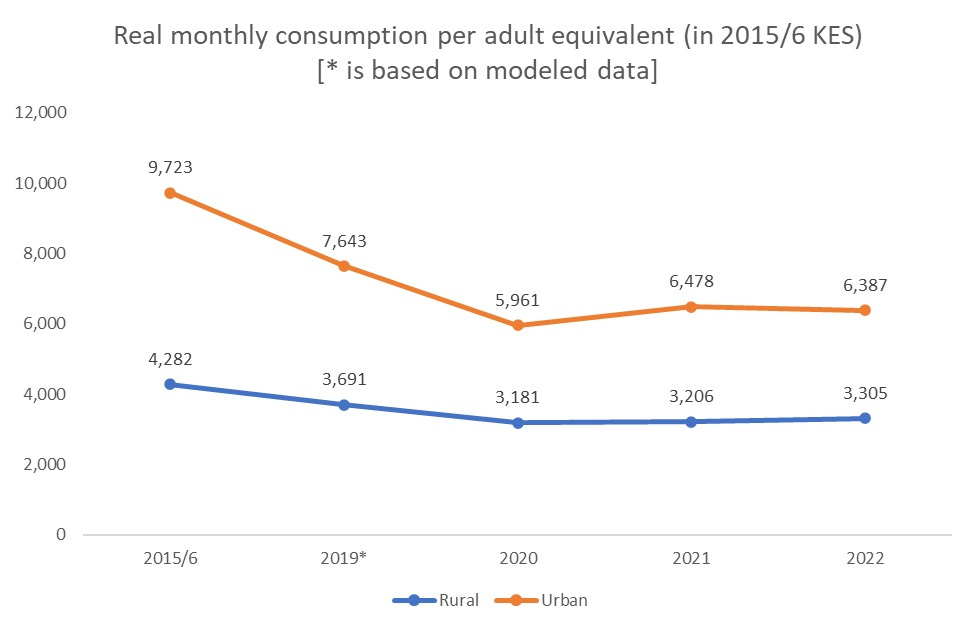

Now we have data from 2022. So far, KNBS has not reported on the overall median consumption levels, but instead provides an urban/rural disaggregation. Here we see slight increases from 2021 in median consumption levels at about 11% in nominal terms (3% real terms) for rural households and 6% nominal (-1% real) for urban households. Poverty and hardcore poverty both rose.

The provision of consumption data broken down by rural and urban areas prompted me to look at longer term trends through that lens. That analysis shows that real consumption has fallen even more steeply (down 34%) in urban areas than rural areas (down 23%) between 2015/6 and 2022. Only the top 20% of Kenyans were consuming more than KES 16,903 ($130) per month in urban areas or KES 7,360 ($57) in rural ones in 2022.

This stark reality ought to be front page news. It ought to foreground all of our conversations about development, whether we’re talking about technology, energy, jobs, finance, or women’s economic empowerment. The reality is that many Kenyans are stagnating at very low levels of economic well-being. We’re witnessing the dream of a growing middle class fading away as well being particularly among the slightly better off and among urban workers erodes. In that context, where does real, poverty reducing growth come from?

There is so much more I could say about this, but why don’t you chime in. Let us know what this means to you in the comments.

References

• 2015/6 Kenya Integrated Household Expenditure and Budget Survey – Basic well-being report: https://statistics.knbs.or.ke/nada/index.php/catalog/13/download/60

• 2019 Kenya Continuous Household Survey https://www.knbs.or.ke/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/The-Kenya-Poverty-Report-2019.pdf

• 2020 Kenya Continuous Household Survey file:///C:/Users/julie/Downloads/Poverty%20in%20Kenya%20-%202020%20Report%2007062023%20(1).pdf

• 2021 Kenya Continuous Household Survey https://statistics.knbs.or.ke/nada/index.php/catalog/123/related-materials

• 2022 Kenya Continuous Household Survey https://knbs.or.ke/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/The-Kenya-Poverty-Report-2022.pdf